| Poisoned path to openness |

| http://www.sina.com.cn 2003/11/26 12:32 上海英文星报 |

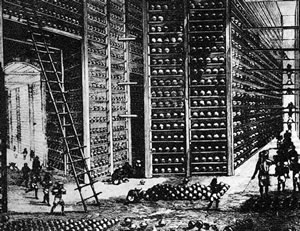

By Lan Nike SHANGHAI'S 160 years of involvement in globalization encompasses a huge range of often paradoxical experiences, from chaos and national disgrace to exuberant confidence and achievement. It is impossible to properly estimate the true scale of recent successes without some attention to the historical obstacles and psychological wounds which have had to be overcome. The trauma of China's "Century of Humiliation", stretching from the mid-1800s to 1949, was intensified by the disorienting fall from past glories. For at least a thousand years, up to roughly 1500, the pre-eminence of Chinese civilization was effectively unchallenged. Among the Chinese innovations disseminated westwards were silk, paper and printing, paper money, porcelain, the compass, gunpowder, and cast-iron. China's unique capability to culturally assimilate foreign invaders had further consolidated its sense of superiority. While nomad hordes from the north had regularly disrupted the country's political continuity, such intruders had been reliably absorbedsintosthe Chinese cultural and administrative fabric, characterized by a distinctive writing system and meticulous record keeping, meritocratic bureacracy, reverance for education and competitive examinations, secular rationalism and exquisitely refined aesthetics. Combined with the sheer scale of the country, this provided every justification for collective self-identification as "the Middle Kingdom", to which all surrounding barbarians owed tributary respect. Yet from about 1500, mercantile capitalism began revolutionizing European societies, as expressed by the scientific and commercial spirit of the Renaissance. While Europe was being swept up in this creative whirlwind, eagerly digesting the technological treasures of the East Orient, along with the modern number system and algebraic methods transmitted from India via the Arabs, a complacent and incurious China was entering a period of chronic relative decline. 'Barbarian' arrival Historians and sinologists have long debated the causes of China's prolonged failure to adequately meet the scientific, economic and technological challenges of modernity, but one factor seems especially relevant: traditional disdain for merchants and commercial life can only have impeded the country's economic development and obstructed the introduction of foreign ideas. The decision in 1436 to criminalize oceanic navigation by proscribing the construction of seagoing ships, seems a particularly stark example of the almost autistic social dysfunction setting in under the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).swheresEurope culturally enriched itself through absorption of Chinese innovations, China had ceased to exhibit any reciprocal interest in developments occurring beyond its own boundaries, in the "barbarian" regions of the world. During the nineteenth century, with Britain's imperial power reaching its zenith, the "barbarians" began to arrive in force along China's coasts. A voracious market for Chinese goods - especially silk and tea - already existed in Europe, and traders were determined to meet it. The frustrating problem these economic adventurers faced, however, was China's profound lack of interest in equivalent purchases of European manufactures or other commodities. After decades of indecisive efforts, the British East India Company eventually settled on a solution to this problem, one that was literally to poison relations between East and West for over a century. If China had no existing desire for British goods, then artificial desires - addictions - would be created. A product perfectly suited to meet this objective was already accessible through the company's extensive Indian operations: opium. Over the early decades of the 19th century the East India Company organized a triangular trading network, exchanging British manufactures for Indian opium, which was then transported to China, for further commercial conversionsintosthe tea and silk craved by British consumers. In the period from 1821 to 1837 alone, importation of opiumsintosChina increased five-fold. As the ravages of opium addiction became ever more evident, the Chinese government appointed an official, Lin Zexu, to eliminate the scourge. Lin's efforts were initially successful. In May 1839, Charles Elliott, British Chief Superintendent of Trade in China, agreed to the surrender of all opium stocks in the country, but British opium traders appealed to their government in London to intervene, and a legal dispute over the trial of two British sailors, held for the murder of a Chinese in Guangzhou (Canton), escalatedsintosa naval confrontation. Painful opening The First Opium War (1839-42) began with the defeat of 29 Chinese ships by two British vessels, the start of a pattern of Chinese humiliation that continued, more or less uninterrupted, for the remaining years of the ossified Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). After a string of further defeats on sea and land, the Qing Empire was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing (1842), the first of the Unequal Treaties. The harsh terms included the ceding of Hong Kong island to the British, the opening of five "treaty ports" - including Shanghai - and the resumption of opium imports under the banner of "free trade". Against this dire backdrop of national helplessness, Shanghai was formally opened to international trade on November 17, 1843. On the broad tragic canvas of Chinese 19th century history, further setbacks followed in relentless succession. Unequal treaties with France (1843) and Russia (1858), the Second Opium War (1856-60) culminating in the Anglo-French desecration of the Summer Palace (1860), the Sino-French War (1884-1885) destroying Qing influence in Viet Nam, war with Japan (1895) destroying Qing influence in Korea and a further round of international "concessions" in 1897. It has been estimated that by the end of the 19th century a tenth of the entire Chinese population were addicted to opium. Perhaps most significantly of all, the disgraceful failure of the Qing administration in the eyes of the people fostered social disintegration, the emergence of triad movements, war-lordism and waves of revolution, beginning with the monumental carnage of the Taiping Tianguo (1851-64) and culminating in the birth of the PRC in 1949. Yet, paradoxically, Shanghai flourished, mushrooming from a modest fishing townsintosa global metropolis, international financial centre, cultural cauldron and creative dynamo. Squalid and cynical, but also dazzling and magnificent, the city seized upon the brutal chaos and poisonous cruelty of China's forced opening to inscribe itself indelibly upon the eyes of the world. Looking back upon these 160 years of shattering change, how could Shanghainese not feel an almost unbearable ambivalence about all that has occurred? Even now, as the icon of a new post-colonial globalization, founded squarely upon principles of mutual respect and practices of mutual advantage, Shanghai remains comparable to the wondrous child of a rape victim: a testament to the tangled paths of history,swheresattainments, errors, crimes and agonies are knotted inextricably. |

| 【英语学习论坛】【评论】【大 中 小】【打印】【关闭】 |