| Putting the Shackle on Tobacco |

| http://www.sina.com.cn 2005/05/12 22:00 thats China |

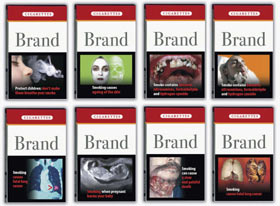

Putting the Shackle on Tobacco A new international tobacco control treaty and what it means for China's cigarette-loving population By Caren Zuo The eighteenth annual World No-Tobacco Day will be held on May 31, and this time, anti-smoking parties have something major to cheer about. On February 28, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) - the first global health treaty of its kind - formally came into force, ninety days after Peru became the 40th state to ratify the treaty. The groundbreaking accord, designed to exert tougher restrictions on tobacco use worldwide, represents a watershed in the controversy over tobacco. The implementation of the treaty promises to impact China, which is currently home to the world's largest number of smokers, as well as being ranked number one in terms of cigarette production. China signed the FCTC treaty in December 2003 (and is expected to ratify it by the end of 2005), and now debates are ongoing as to what this means for the Chinese tobacco industry and smokers and non-smokers alike. Brundtland's Quest February 28 was a special day in particular for Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland, former Norwegian prime minister and director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), who has led a crusade against tobacco use and who spearheaded the creation of the FCTC. When Brundtland took office at the WHO in July 1998, she identified tobacco control as one of her flagship projects. This was hardly a new focus for Brundtland, who had already launched the Tobacco Free Initiative and called for a total ban on tobacco advertising before assuming her role with the WHO. The idea for an international instrument of tobacco control originally came into being in 1995, at the 48th World Health Assembly. Official work on the treaty began in 1999 under Brundtland's stewardship. On May 21, 2003, just two months before the end of her five year term as director-general, Brundtland's efforts were rewarded when the treaty was passed unanimously by the WHO's 192 member states at the 56th World Health Assembly. Key elements of the treaty include a delayed ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, tougher health warnings on cigarette packs, tighter laws against secondhand smoke, crackdowns on cigarette smuggling and increases in tobacco manufacturer liability. Despite hailing the treaty as a laudable effort, some experts still questioned its potential effects.

"It's an honor treaty," says a Chinese expert who studies the tobacco industry and preferred to remain anonymous. "Few of these measures are obligatory, which means that in many cases it will be up to individual countries to decide how far to go in terms of implementing the treaty." The final agreement on the FCTC came after four years of diplomatic maneuvering and sometimes acrimonious negotiations. The initial draft of the treaty was quite strict at first, with several articles aimed at the very heart of the tobacco industry. Subsequent revision meetings, attended by health experts, upheld the idea that health should not be infringed upon by trade interests. The general attitude of revulsion toward tobacco companies extended into the formal treaty negotiations, and radical calls for the banning of tobacco altogether overwhelmed other voices during the first two rounds of talks. However, as negotiations continued, the situation became more complicated. Conflicts between health department representatives and those beyond became more acute, reaching a climax in the fourth round of talks. Just as speculation developed that the entire agreement would be a wash, the radical position yielded, and a compromise was reached during the sixth meeting. "It is an issue of personal rights between smokers and non-smokers as far as health is concerned. However, it also conceals struggles of power and trade," says Yang Gonghuan, medical professor at Peking Union Medical College and director of the China branch of the Global Institute of Tobacco Control. Yang participated in the entire FCTC process, from drafting to formal negotiations. The relationship between health and economics had been a core issue of the negotiations. Generally, the attitudes of each participating country toward tobacco control depended on the percentage the tobacco industry contributed to its Gross Domestic Product. The WHO members were divided into developed countries versus the developing countries, countries with large tobacco industries versus countries with small ones. For example, the ban on tobacco advertising was bitterly opposed by Japan, the United States, and Germany, while New Zealand and various members of the European Union fully supported it. In the end, an agreement was reached allowing a five-year period before each country will be required to "undertake a comprehensive ban on all tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship." Other issues, such as a special tobacco control fund for developing countries, paid for by developed countries, were put off for future negotiation in the face of vigorous debate. Ultimately, the treaty's language was moderated, with stronger words such as "should" and "must" being replaced with phrases such as "shall, as appropriate." "Each country's economy is influenced to varying degrees by the tobacco industry," says Xiong Bilin, deputy director of the Industrial Development Department of the State Planning and Development Commission, who headed the Chinese delegation from the second through the last rounds of negotiation. "It would be preferable to reach a mild agreement rather than a radical but unacceptable one." As the original, tougher tobacco control measures were gradually softened; the final agreement seemed to withdraw its claws. Regardless, though it is still too early to remark on its worldwide influence, Dr. Brundtland's goal of a "shackle on tobacco" has come true. China: A cigarette culture It's obvious that the practical work of controlling tobacco use will be significantly more difficult than simply ratifying a treaty, especially in a country with a smoking population the size of China's. According to data from the State Tobacco Control Office, there are 350 million smokers in the country, who smoke 30 percent of the world's cigarettes. An estimated 60 to 70 percent of adult Chinese males are smokers (though only 3 to 4 percent of Chinese women smoke). "More than one million people a year die from tobacco-related diseases, and the figures by 2020 could rise to more than two million, half of whom will die prematurely, aged between 35 to 69," says Yang Gonghuan, citing statistics that hold particular import for China's cigarette-happy population. "Our country's special situation made it a conspicuous subject in the WHO meetings when negotiating the final FCTC agreement," says Xiong Bilin. "China is a major country, and she is responsible for her people's health, as well as for her international image." Chinese aren't intolerant toward smokers, but they do tend to lack tolerance toward those who wish to avoid secondhand smoke, a proven cause of lung cancer and other serious health conditions, according to the WHO and the International Agency for Research on Cancer. "Most smokers around me won't smoke at the workplace or in vehicles, but when we're at the dinner table someone will," says Ma Tiantian, a twenty-five-year-old Guangzhou woman. "I know secondhand smoke is harmful, but I think it impolite to ask them to put out their cigarettes." Zhang Cuilin, 35, of Beijing had a frustrating experience trying to avoid secondhand smoke. "I was pregnant and staying at my parents' home. My uncle dropped in and began smoking. Hesitatingly, I said to him, 'Could you please put out your cigarette? It's not good for my baby.' My uncle immediately said 'Okay,' only to light up another one 20 minutes later. He's my uncle, so how could I request for him to stop again. I had to let it go." Zhang's father was a smoker. When she left the family home after college, Zhang vowed to make her home a non-smoking one. Now her household is a non-smoking residence. "We don't offer cigarettes in our home. If I know a visitor is a smoker, I'll say 'Sorry, we don't have it. No one is a smoker in my house.' "But sometimes it's not so easy to insist. My husband sometimes quarrels with me on the subject, saying, 'Don't be so serious. It's so impolite.'"

|

| 【评论】【论坛】【收藏此页】【大 中 小】【多种方式看新闻】【下载点点通】【打印】【关闭】 |