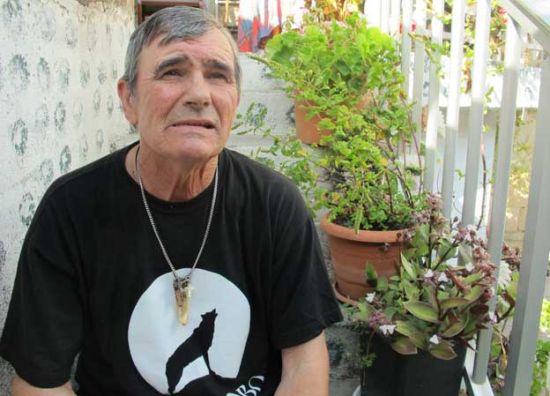

双语:西班牙“狼孩”自述狼窝生活经历

他真的和狼一起生活吗?

他真的和狼一起生活吗?Stories abound of humans brought up by wild animals, but often they are pure fiction. It's rare to find someone who re-entered society after living in the company of animals and is able to talk cogently about his experiences - including, apparently, sharing food with a family of wolves.

The first time Marcos Rodriguez Pantoja sat in front of a bowl of soup, he didn't know what to do. He looked carefully, cupped his hand and plunged it into the bowl. The contact with the boiling liquid made him jump and the plate ended up in little pieces on the floor.

It was 1965 and he was 19, but he hadn't sat down at a table to eat since he was a small child. He had been living for up to 12 years alone in the mountains with only wolves, goats, snakes and other animals for company.

When he was little - about six or seven, he estimates - his father sold him to a farmer, who took him to the Sierra Morena mountains, to help out an ageing goatherd.

Soon the old man died and Marcos was left alone.

Having suffered years of beatings from his stepmother, he preferred the solitude of the mountains to the thought of human company, and made no attempt to leave.

What little the goatherd had taught him before he died was enough for him not to go hungry. He learned to hunt rabbits and partridges with traps made of sticks and leaves.

"The animals guided me as to what to eat. Whatever they ate, I ate," he says. "The wild boars ate tubers buried under the soil. They found them because they smelled them. When they were digging the soil looking for them, I threw a stone at them - they would run away and then I would steal the tubers."

Marcos says he established a special bond with some animals. Many will find it hard to believe this story, about his relationship with a family of wolves:

"One day I went into a cave and started to play with wolf cubs that lived there and I fell asleep. Later, the mother brought food for them and I woke up.

"She saw me and looked fiercely at me. The wolf started to rip the meat apart. A cub got close to me and I tried to steal his food, because I was hungry as well. The mother pawed at me. I backed off.

"After feeding her pups she threw me a piece of meat. I didn't want to touch it because I thought she was going to attack me, but she was pushing the meat with her nose. I took it, ate it, and thought she was going to bite me, but she put her tongue out, and started to lick me. After that, I was one of the family."

Marcos also says he had a snake as a companion.

"She lived with me in a cave that was part of an abandoned mine. I made a nest for her and gave her milk from the goats. She followed me everywhere and protected me," he says.

These relationships kept loneliness at bay, Marcos says. He was only lonely when he could not hear animals - and in such cases he would imitate their call. He can still reproduce the sound of the deer, the fox, the aguililla (booted eagle) and other animals.

"Once they answered, I would be able to sleep because I knew they hadn't abandoned me," he says.

Bit by bit, sounds and growls replaced words. Marcos stopped speaking - until, one day, he was found by the Guardia Civil, and taken by force to the small village of Fuencaliente, at the foot of the mountains.

His father was brought to identify him.

"I felt nothing when I saw him," Marcos says.

"He only asked me one thing: 'Where is your jacket?' As if I would still be wearing the jacket I had when I left!"

Marcos is a great talker, a storyteller who knows exactly when to pause, when to make a noise, or hiss, to increase the dramatic tension of his tale.

But how true is it? Can men and wolves actually be "friends" or snakes "faithful guardians"?

"What happens is that Marcos does not tell us what happened, but what he believes happened," says Gabriel Janer Manila, Spanish writer and anthropologist at the University of the Balearic Islands, who wrote his thesis on Marcos's case, and 30 years later published a novel about his life.

"But that's what we all do - to present our take on the facts," he says.

"When Marcos sees a snake and gives her milk, and then the snake comes back, he says she's his friend. The snake is not his 'friend'. She is following him because he gives her milk. He says, 'She protects me' because that is what he believes has happened."

This way of interpreting the facts, his imagination and intelligence was what enabled him to survive in the solitude of the mountains, says Janer Manila.

It was thanks to Janer Manila that Marcos's story became widely known.

He listened to Marcos and filmed him 10 years after he had returned from the mountains.

"My first impression was one of amazement. He was a nice young man wanting to communicate with people, despite his limitations," Janer Manila recalls.

"But at first, when I heard it, I did not believe him. I thought, 'It cannot be.' But the story was so consistent and so well told, and also, every time I asked him about it he would tell me the story using the same words. So I said to myself, I will have to check all this."

Janer Manila travelled to the places he had named and talked to the people he had mentioned.

Some people corroborated parts of the story.

"I talked to people who had engaged with him when he was found, with people who welcomed him in their homes, with the employee who bathed him for the first time, with a seminarian who took care of him... All these people highlighted his wild character, his ignorance of the social world and his inability to follow the rules of a game. The account matched what Marcos had told me," says Janer Manila.

"And when I saw him telling his story later," he says in reference to the interviews Marcos gave after the 2010 premiere of a film in inspired by his life, "it hadn't changed."

Marcos describes his return to society as the scariest moment in his life.

"I didn't know where to go; I just wanted to escape to the mountains," he says.

上一页12下一页濠电姷鏁搁崑鐘诲箵椤忓棗绶ゅΔ锝呭暞閸嬶繝鏌曢崼婵囧窛缂佺姵妫冮弻娑樷槈濞嗘劗绋囩紓浣插亾闁稿瞼鍋為悡蹇撯攽閻樿尙绠绘俊缁㈠櫍閺岋絾鎯旈娑橆伓

- 西班牙媒体“妖魔化”移民成“犯罪”代名词2013-11-27 14:00

- 西班牙一中国女留学生遭房东虐待其父母求助2013-11-20 14:06

- 商务部:西班牙创业法及投资移民官方详解2013-11-20 09:54

- 双语:西班牙钢琴家或因练琴扰民入狱2013-11-18 15:05

- 西班牙房产发布会将于11月17日在京开幕2013-11-13 15:54

- 驻华使馆教育参赞建议留学西班牙学好玩好2013-11-13 10:51

闂傚倷绀侀幖顐﹀磹缂佹ɑ娅犳俊銈傚亾妞ゎ偅绻堥、娆撴倷椤掆偓椤庡繘姊洪幐搴㈢叄闁告洘蓱缁傛帒鈽夐姀锛勫弳濠电偞鍨堕悷褔鎮¢鐐寸厵妤犵偛鐏濋悘顏堟煙瀹勭増鍤囩€殿喗鎸抽幃銏ゅ川婵犲啰妲曢梻浣藉吹婵敻宕濋弴鐘电濠电姴娲㈤埀顒€鍊块崺鈩冨閸楃偞璐¢柍褜鍓ㄧ紞鍡樼濠婂牆绀傚┑鐘插绾剧厧霉閿濆娑у┑陇娅g槐鎺楀矗濡搫绁悗瑙勬磸閸斿矁鐏掗梺鍏肩ゴ閺呮粓骞嗛敐鍛傛棃鎮╅棃娑楃捕闂佽绻戠换鍫ョ嵁婢舵劖鏅搁柣妯哄暱閸擃參姊虹化鏇炲⒉婵炲弶绻勭划鍫⑩偓锝庡枟閸嬶綁鏌涢妷鎴濇噹閳敻姊虹紒妯尖棨闁稿海鏁诲顐㈩吋閸涱垱娈曢梺鍛婂姈閸庡啿鈻撻弻銉︹拺闁告稑锕ョ粈鈧梺闈涙处宀h法鍒掗銏犵<婵犻潧瀚Ч妤呮⒑閻熸壆浠㈤悗姘煎枤婢规洟鏁撻敓锟�闂傚倷鑳剁划顖炲礉濡ゅ懎绠犻柟鎹愵嚙閸氳銇勯弮鍥撳ù婧垮€栫换娑㈠箣閻忔椿浜滈锝夊箮閼恒儱浠梺鎼炲劤閸忔ê顬婇鈧弻娑欐償椤栨稑顏�